Fantasies of the Universe

Il Foglio, Milan, 5 March 2016

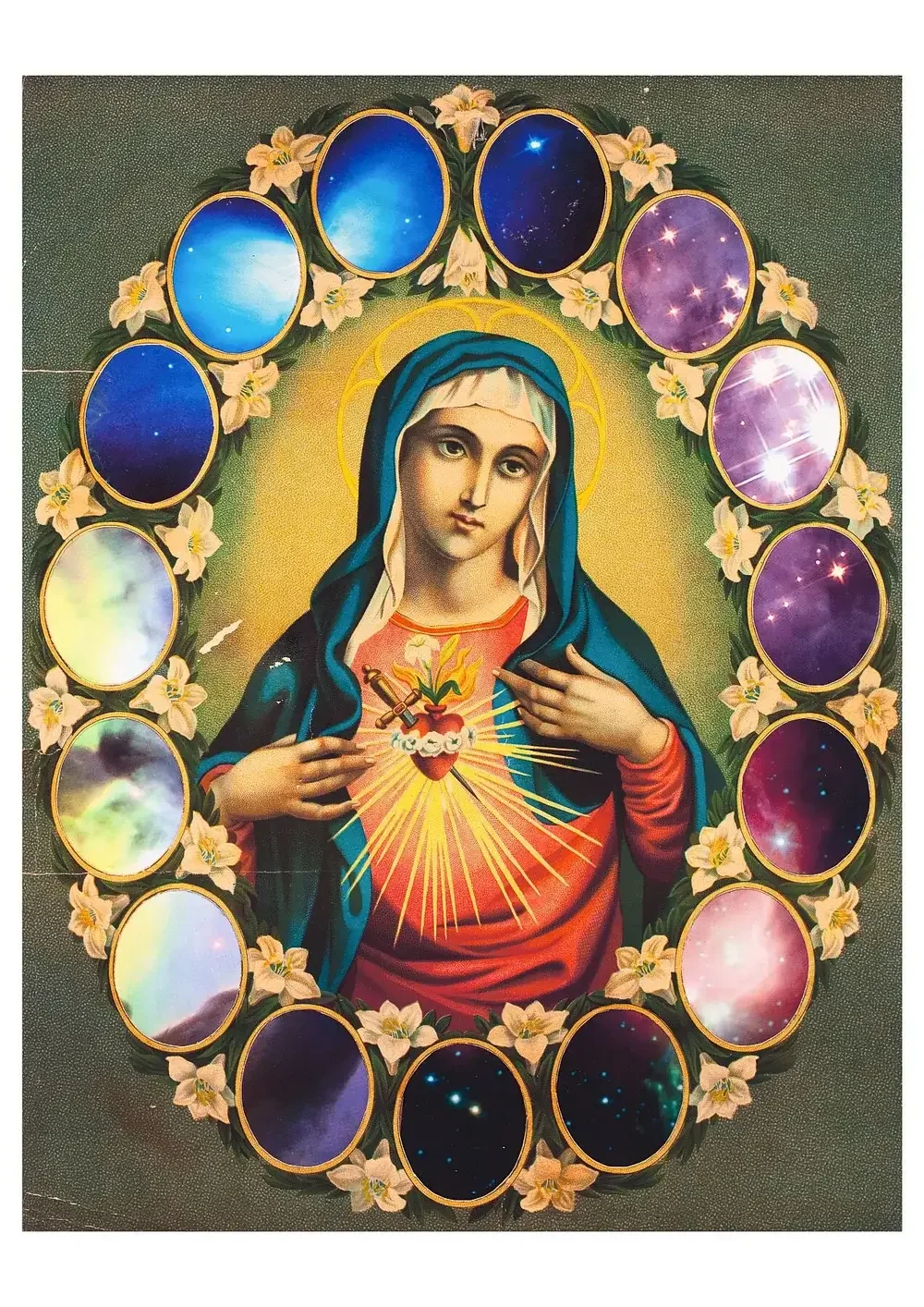

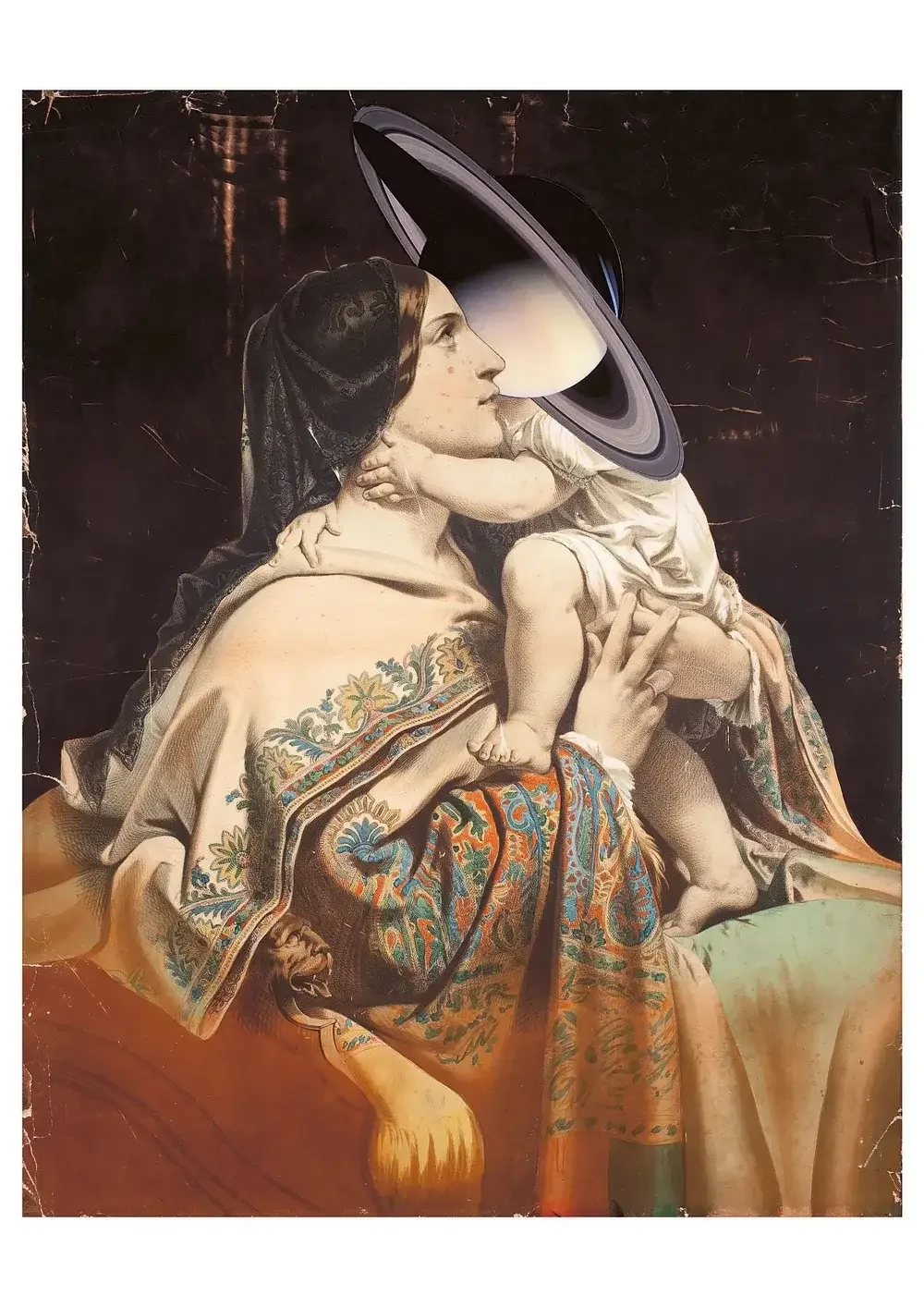

The collages featuring images of deep space exploration were inspired by the artist's friendship with Palermo gallery owner Francesco Pantaleone and the shop selling religious furnishings that has belonged to his family for generations.

By Valentina Bruschi

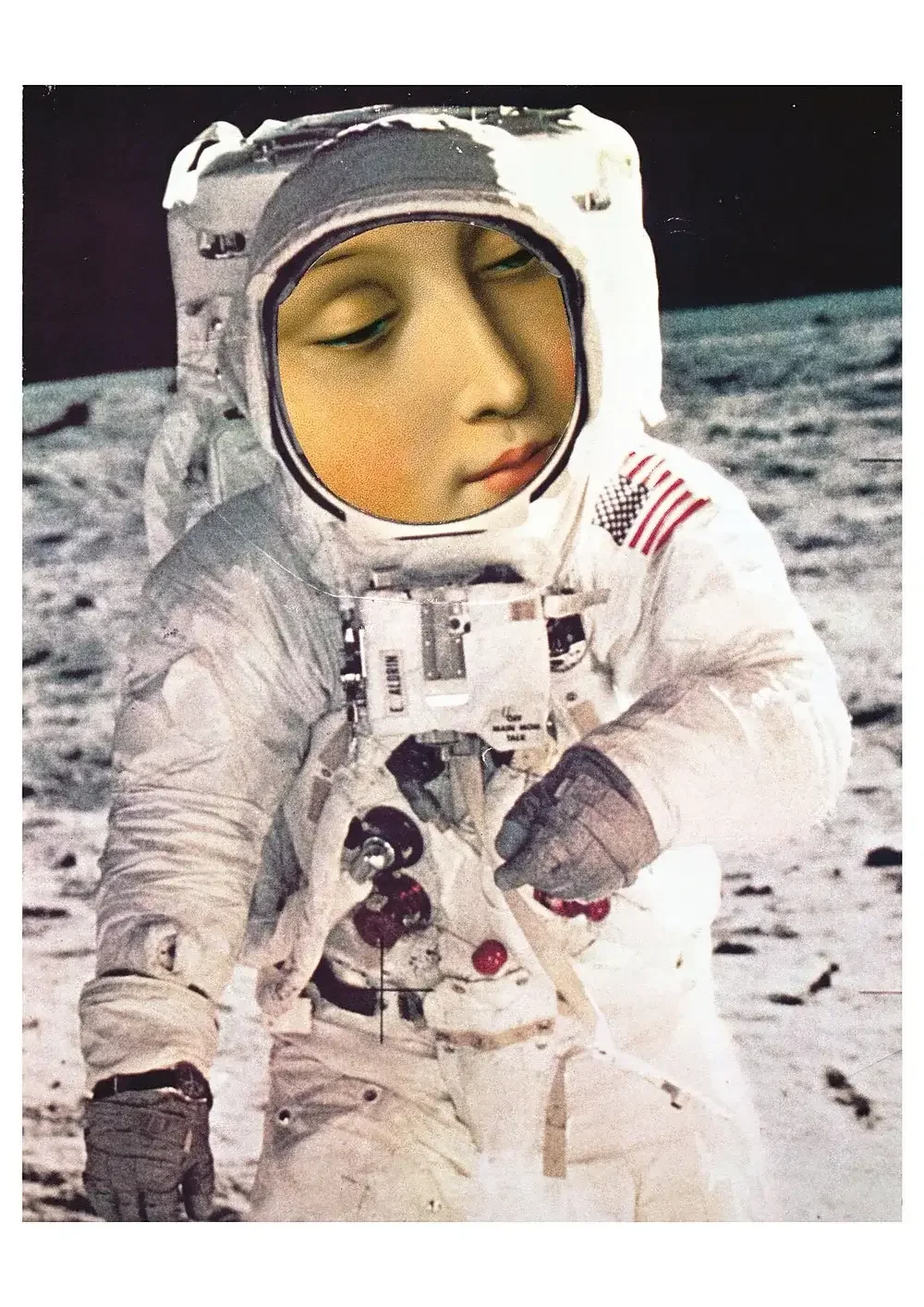

… The theme of infinite space has been a recurring element in Mir's research for over fifteen years and a stimulus for the artist's critical reflection on major historical events. On 28 August 1999, around the 30th anniversary of Neil Armstrong's famous first walk on the moon, without a budget because she was at the beginning of her artistic career, Aleksandra Mir managed to convince some bulldozer operators working at a nearby factory to help her transform a beach on the North Sea in the Netherlands into a lunar landscape with hills and craters.

At sunset, the artist, followed by a group of people in swimsuits, climbed to the top of the highest dune to the rhythm of a bongo drum, planted an American flag, and proclaimed herself “the first woman on the moon”. The artist, having previously alerted the local media, documented the event, which was filmed by three local television stations, thus managing to introduce the female element into the then entirely male-dominated history of space travel.

The beach was cleared that same evening, but the performance remains in the media's memory, through a video and numerous images, as well as pseudo-relics such as the original flag. Shown in various international exhibitions, the film taken from this action-fiction, First Woman on the Moon, was acquired for the permanent collections of the Tate Modern in London and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, which historically validated Mir's performance.

This “obsession” with space is the essence of numerous works, both monumental sculptures, such as Gravity (2006), in which Aleksandra constructed a giant (obviously non-functional) missile 22 metres high using industrial debris, and the series of collages, The Dream and the Promise, created in Palermo, where the artist lived for five years, from 2005 to 2010.

Aleksandra Mir's “Italian period” was very fruitful for the artist's research, who created several works in which subjective reflections are translated into a fresco of our country, which becomes - in artistic transfiguration - a universal model.

The collages featuring images of deep space exploration were inspired by the artist's friendship with Palermo gallery owner Francesco Pantaleone and the shop selling religious furnishings that has belonged to his family for generations.

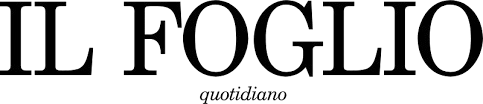

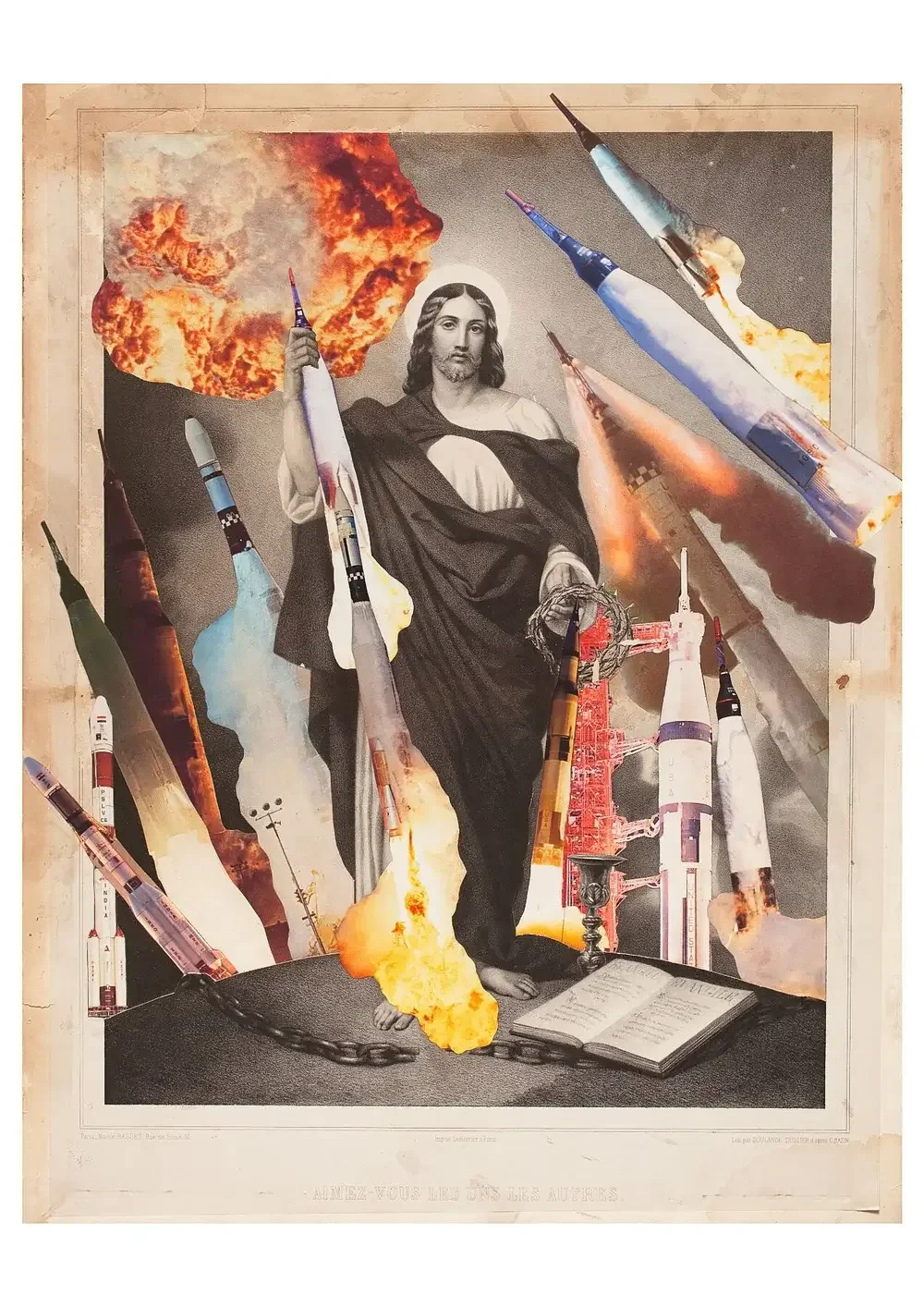

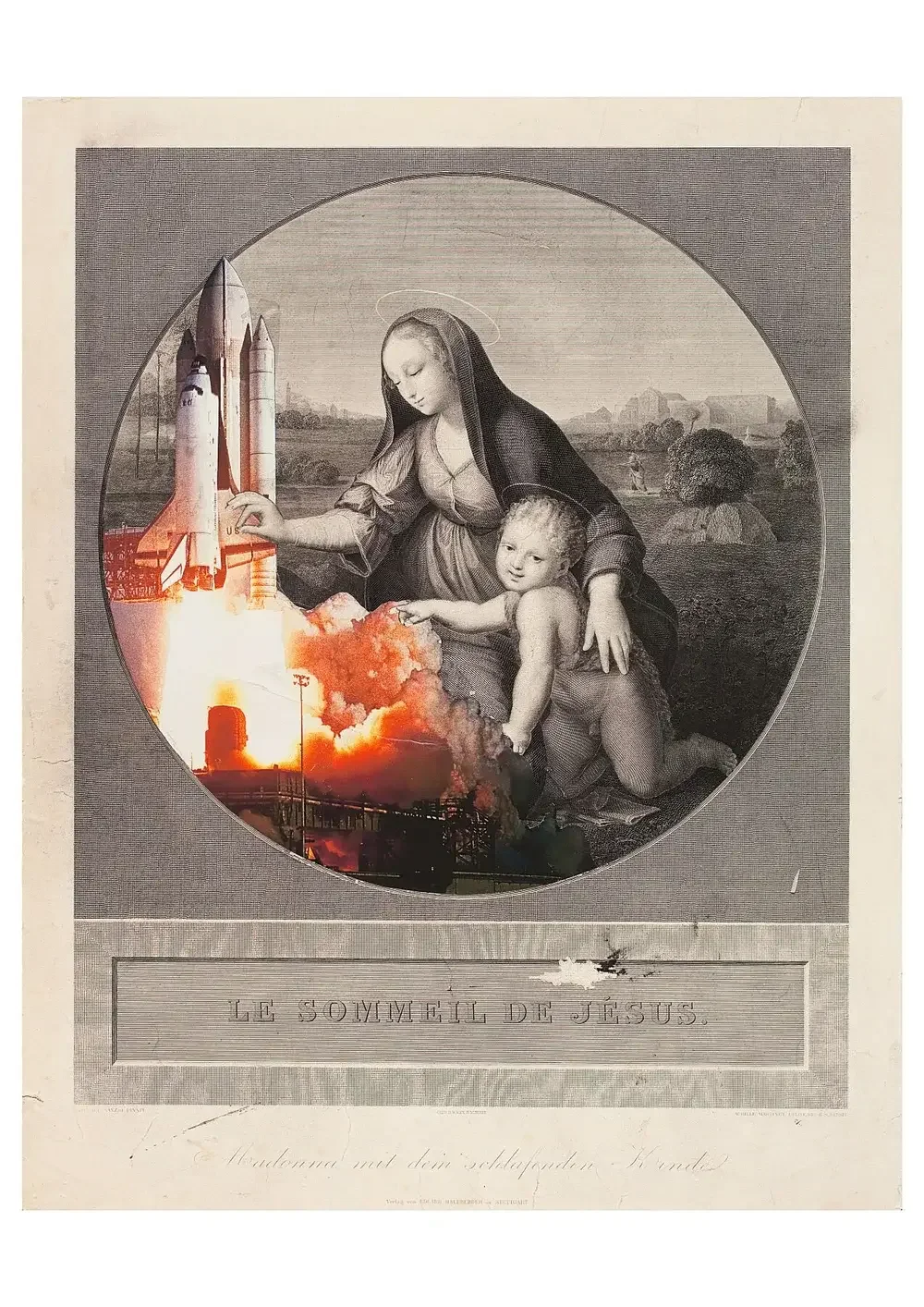

The artist superimposes sacred images onto those of rockets, satellites, planets and space probes, and vice versa. Holy cards and mementos of first communions or baptisms are combined with clippings from 1970s American magazines on space exploration. The faces of saints, surrounded by halos, replace the heads of astronauts protected by helmets, while the smoke from departing rockets overlaps with the trail of a comet or the pattern of celestial clouds on which angels travel.

An iconographic and cultural encounter/clash, as when the artist from the United States arrives in Italy and, as is often the case in her work, reflects on aspects of popular culture to create visual short circuits that challenge our deepest convictions. “I thought,” says the artist, “that since saints and astronauts share the same space, it was important to introduce them to each other!”

It is obvious that Aleksandra Mir's productions are not created within the confines of traditional artistic practices. In fact, Mir overturns the belief that a good work of art is one created in a defined space and delivered to the quiet viewing of the public.

Perhaps, however, more than for her large installations, such as Plane Landing – a life-size inflatable aeroplane that she took around the world, from Zurich airport to the Louvre Pyramid, photographing it in what she calls 'a permanent act of landing' – she will be remembered for her manual on how not to cook, published as an artist's book in 2009 (and later reprinted by Rizzoli), which entered the permanent collection of MoMA.

Conceived after a disastrous dinner party that the artist organised in her flat in the historic centre of Palermo, it draws inspiration from a personal defeat to create an artistic project with a global reach: The How Not to Cook Book – Lessons learned the hard way, in which Aleksandra involves her friends in different countries around the world in the editorial coordination and collection of a thousand testimonials and tips on how absolutely not to cook.

The large installation, Triumph, is also the result of a collaborative project, created with over 2,500 trophies collected by the artist through an anonymous advertisement published in the Giornale di Sicilia: “old sports trophies wanted.” Cleaned and catalogued, these trophies dating from 1940 onwards represent all kinds of sports and form the structure of a dazzling sculptural installation.

Objects that celebrate personal victories become metaphors for a nation. By collecting these fetishes, the artist came into contact with people who responded to the advertisement and who, perhaps, wanted to emancipate themselves from the past or get rid of a cumbersome object that was now just gathering dust. In addition to this psychological aspect, the large archive work deals with the passion for sport in Italy, considered “like a religion”, says the artist.

Originally commissioned and exhibited at the Schrin Kunsthalle in Frankfurt in 2009, Triumph gained global recognition at the 2012 London Olympics, as part of the collective exhibition ‘Pursuit of Perfection: The Politics of Sport’ at the South London Gallery. Like many of the artist's works, it is a piece that originated in a local context but acquires value and meaning when exhibited to an international audience.

The same meaning can be attributed to the sculpture created from the Fiat 600, the small car in which the artist travelled the length and breadth of Sicily during the period he lived in Palermo. A functional object and a source of affection, transformed into a work of art.

Before being exhibited at the Magazzino d'Arte Moderna in Rome and in the 2012 edition of Art Parcours, a special section of the world's most important contemporary art fair, Art Basel, the car's last journey was to the garage of a Roman mechanic who transformed it into a work of art, following the artist's instructions and design.

The car was cut up and reassembled into a sort of 2/3 car, fully functional but reduced to a single-seater at both the front and rear. It is a clear homage to the famous work, La DS, by the renowned Mexican artist Gabriel Orozco, a classic of 1990s art, exhibited at the 2003 Venice Biennale.

The difference between the two works is clear: while the Citroën has been perfectly reconstructed by expert designers, as if its reduction had been carried out by the hand of a surgeon, the Fiat proudly displays the scars of its welding, which give it “dignity”. 'An ugly duckling', says Aleksandra Mir, “whose strength lies in the aspiration it expresses”.

Just as the cups manifest individual ambition – and, taken together, collective ambition – so the car reflects the aspirations of Italian society in the 1960s with its petty bourgeois myths of comfort and well-being. When the artist drove it illegally through the centre of Rome, taking photographs in front of the most important monuments, the car aroused the curiosity of the traffic police who watched it, smiling and empathising with an object that was clearly “out of the ordinary” but linked to the collective memory.

And it is always a car – this time at the opposite end of the social scale from the small car – a 1977 Rolls Royce Silver Shadow, that forms the core of the project, Sicilian Pavilion: a nomadic and independent pavilion on four wheels, created “partly for fun and partly as a provocation”, which presented itself as an uninvited participant at the 52nd edition of the Venice Biennale in 2007.

On board the luxurious car is a group of special passengers: Aleksandra Mir, the driving force behind the project, who donated her works to the collector Marion Franchetti, who financed it; the curator Paolo Falcone, acting as organiser and chauffeur; and two young Sicilian artists, Luca De Gennaro and Salvatore Prestifilippo.

Setting off together from the port of Palermo, they boarded the ferry to Naples and, in three days of travel, covered 200 nautical miles and 800 kilometres, arriving in time for the opening of the famous lagoon festival to reaffirm the creative vitality of the South and shake up the apathy and indifference of its institutions.

The poetics of the project are expressed in an artist's book, produced by the Sambuca Foundation, which collects all the images of the journey: 'the Sicilian Pavilion simultaneously presents new and energetic talents as a melancholic yet hopeful meditation on the future of the island.

The fate of the young artists arriving in Venice is deliberately left open: all participants are left to fend for themselves, with no money for hotels or official invitations. They initially have to fight and elbow their way through.

It is no coincidence that during the road trip, an established artist – in this case played by Mir – reads aloud to the young punk artist Luca De Gennaro the entire novel The Punk, written by Gideon Sams in 1977, the same year the Rolls Royce was manufactured, which in this role play represents the decadent spirit of the Sicilian aristocracy.

Aleksandra Mir's departure from the island was a loss, even though she left behind a legacy of good practice in deconstructing outdated patterns, using lightness to invent new, freer forms of thought.