Space exploration

as a cultural object

HOW AND WHY SPACE AGENCIES SHOULD ENGAGE WITH ARTISTS

Greater engagement with domains beyond STEM can help space agencies reflect not just on the immediate returns on investment, but our deeper purpose in supporting a deeper understanding of (following Kant) what it true, what is beautiful and what is good.

By Andrew Kuh, Head of International Spaceflight Policy at UK Space Agency

Paper delivered at the 70th International Astronautical Congress

Washington D.C. 21-25 October 2019

Abstract

Space exploration has long provided inspiration for art, from the high-brow to the low; from visual art, to literature, fashion, film: space permeates culture. This “cultural imagination” of space is, however, effectively divorced from the actual reality of space exploration as practised by engineers and scientists today: it might as well exist in a different galaxy.

That the cultural imagination and the concrete reality are quite distinct is not a novel observation. Attempts have been made to address this, but are often stymied by lack of common vocabulary, or a one-sided approach to engagement, or the incompatible expectations and objectives of participants from either side.

Equally, many space/art projects result in an interesting but relatively simplistic exchange of ideas. An instructive parallel can be found in Bernstein’s concept of aesthetic alienation and the argument that in a post-Kantian world, the truth-value of art has been diminished.

But our concrete practice of space exploration presents good reason for the divorce between space-as-cultural-object and actual-space-exploration: on a basic level, when launching expensive things into space, the scientific basis and conventions of testing and qualification are critical to success. No wonder art is relegated to an optional extra.

There are however strategies for fostering meaningful exchange between the arts and the space community. Approaching this challenge from a space agency perspective, this paper examines the conceptual underpinning, practical engagement and exciting outcomes of a recent collaboration between the UK Space Agency and the artist Aleksandra Mir.

Mir proclaimed herself First Woman on the Moon in 1999; in 2017 her Space Tapestry charted a new history of space exploration. Artists have freedom to approach the subject unbound by the constraints of physics or existing technology – but I argue this does not mean that their work demonstrates lesser intellectual rigour or a subordinate truth, and further that the space sector can benefit from a more thoughtful approach to the arts and humanities.

Space agencies are good at utilising the skills of economists, lawyers and artists to achieve specific, narrowly prescribed ends. Working directly with artists in a more open and genuinely collaborative way comes with challenges and risks, but re-thinking the way the space sector is situated in culture can benefit all.

Keywords: space exploration, art, culture, astroculture, aesthetics.

1. Introduction

Two basic types of creation can be distinguished: one, initiated by the conscious mind, serves practical life, so-called, and deals with the concrete visual phenomena; the other stemming from the subconscious or superconscious mind, stands apart from all ‘practical utility’ and treats abstract visual phenomena. We find the concrete element in the sciences and religion – the abstract in art.’ – Kasimir Malevich, The Non-Objective World [1].

Two versions of space exist in parallel: space-as-cultural-object and space-as-concrete-reality. The first can be observed in movies, visual art, music, fashion and elsewhere – this paper is concerned primarily with contemporary visual art, though many of its observations might apply elsewhere.

The second is practised by scientists and engineers, with the results sometimes communicated through the same media, though subject to different forms of narrative, presentation and scrutiny. It has been argued that since Kant, the truth-function of art has been relegated to a separate domain of the aesthetic, in contrast to modern scientific and technological reason [2].

This split, following the lines of Kant’s categorical distinction between the beautiful, the true and the good, has led to an undermining of the perception of art’s function. It can be argued that the separate roles ascribed to art and science underscore the value of each: for Schopenhauer, art goes beyond mere description of the physical and ‘art and aesthetic experience not only provide escape from an otherwise miserable existence, but attain an objectivity explicitly superior to that of science or ordinary empirical knowledge’ [3].

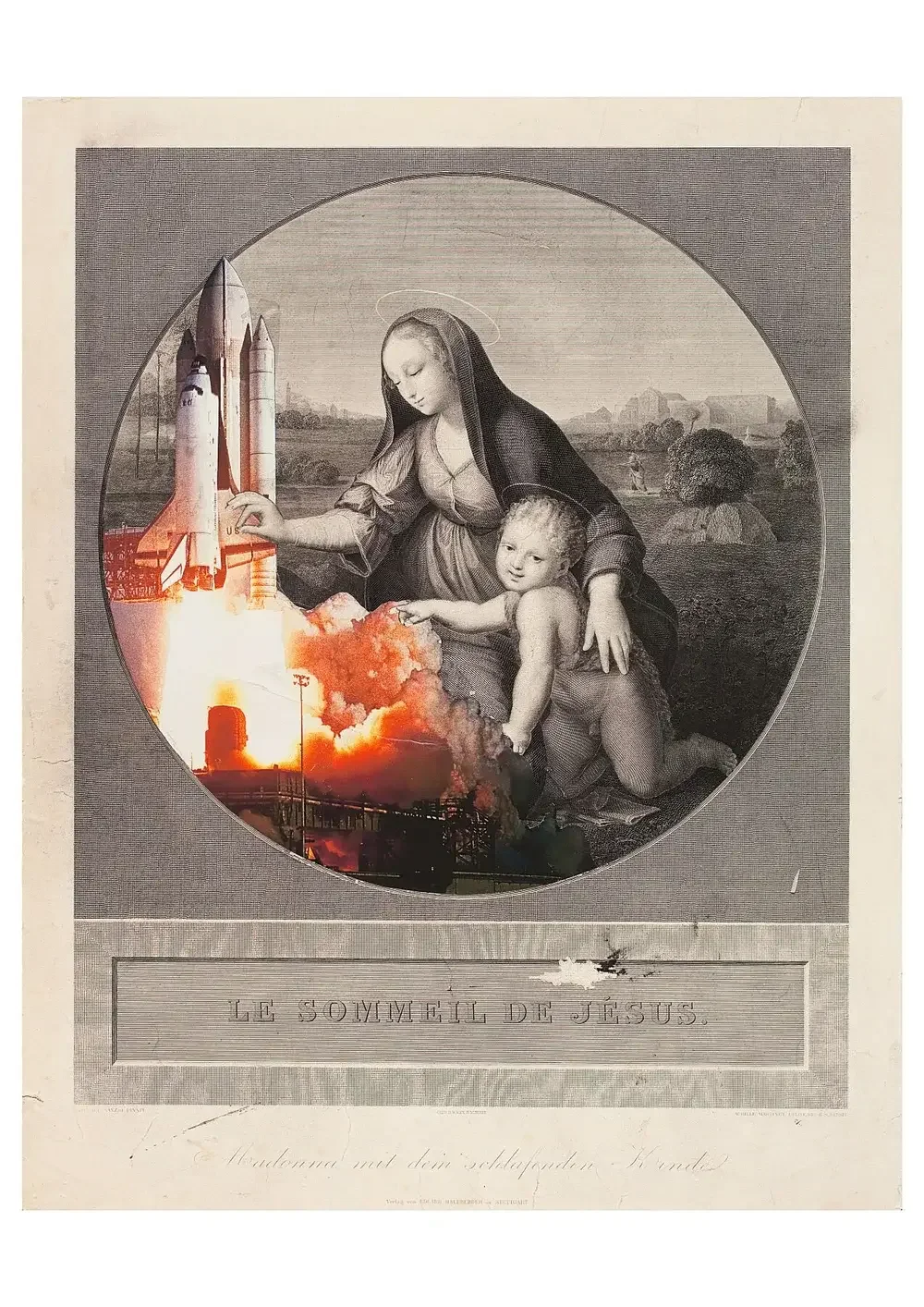

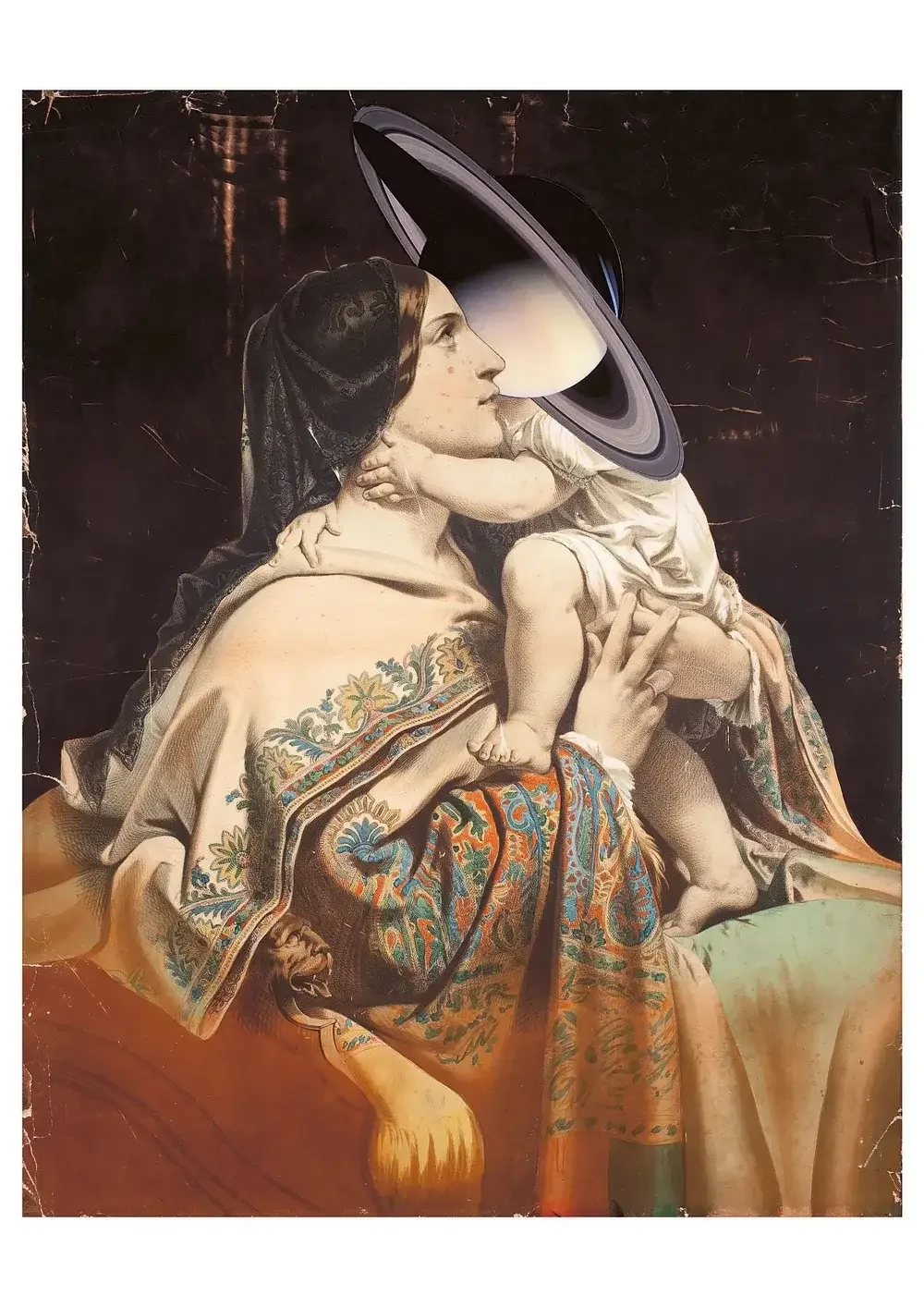

Either way, the separation today appears complete; the distinction absolute. Space-as-cultural-object operates in the aesthetic domain. It has no obligation to aspire to objective truth or empirical accuracy. It sometimes functions as an oblique mirror of the actuality of space exploration: drawing on imagery from actual space missions, but deploying such imagery for a fundamentally different purpose. Space-as-concrete-reality is a pursuit of science and technology.

Space exploration, in particular, relies on human creativity and ingenuity, but its purpose and its success are fundamentally and unavoidably grounded in the observable world: the purpose of space exploration, roughly speaking, is to learn more about the physical universe; critically, successful space missions rely upon an understanding and application of physics.

While the value of space exploration is often presented in terms such as economic value, job creation and technological innovation, the underlying drive for this – the first principle – is curiosity and a desire to better understand the empirical universe. Carl Sagan memorably observed, “I like a universe that includes much that is unknown and, at the same time, much that is knowable.” [4]

It is the pursuit of the knowable which prompts and sustains desire for space exploration. The art-science schism does not mean that our alternate versions of space do not learn from each other. Much science fiction draws directly on what is theoretically possible; design and fashion straightforwardly co-opt the synthetic images of space telescopes.

In return, science fiction is claimed to have predicted and even informed space programmes. Arthur C. Clarke famously popularised the notion of global telecommunications satellites in geostationary orbits with a 1945 essay. There are numerous examples of artists, scientists and engineers collaborating at the cutting edge of their fields. (Arthur Miller’s Colliding Worlds gives an illuminating and encouraging survey of this emerging interdisciplinary field of practice [5]).

I argue that the space sector (by which we mean the scientists, engineers and bureaucrats of industry, research institutes, governments and agencies) can do more to draw on this. Moving beyond superficial or one-way transfer of ideas, there is a vast unrealised value to be gained through engagement with artists in a more reflexive and expansive way.

2. Background

The UK government formally entered human spaceflight for the first time in 2012, with a decision to join the European Space Agency’s (ESA) human exploration and microgravity programmes – ensuring, among other things, British contribution to the International Space Station (ISS). Funding decisions in a government bureaucracy must be based upon clear objectives and a solid rationale – when spending public money, we have a duty to demonstrate value for money and respond to a particular need or requirements.

Space is no different in this respect to other areas of government activity, and a detailed business case was produced, describing the expected economic and social benefits to the UK of investment in human spaceflight. Expected benefits included a boost to UK industry, opening up of new opportunities for UK scientists and, significantly, the opportunity for ‘inspiration.’

2.2 Defining ‘Inspiration’

‘Inspiration’ is a much-used, often poorly defined term in the space exploration community. (There is an irony in witnessing engineers and scientists who often depend upon specific and unambiguous definitions of terms using the term ‘inspiration’ without defining what exactly is mean; sometimes without specifying who, how or what is being inspired.)

Nonetheless, in the context of space exploration, ‘inspiration’ is generally understood as using the excitement generated by exploration programmes and missions to promote certain educational goals. It is this context in which the space sector typically views art.

Art is often seen by space agencies as a means to an end: it is not necessarily considered to be lacking in value, merit or relevance, but it is often seen in utilitarian terms. For example, art is good because it connects to people who might otherwise not be interested to space. Or: art has value because it gets children who are not interested in STEM subjects to think about space.

Or: artists know how to communicate; we should use artists to communicate our science. While there is arguably nothing inherently wrong about viewing art in these terms, a simplistic and reductive notion of the purpose and basis of art – reducing its ‘truth-value’ not just to a different domain but to functional irrelevance – has limited the ways in which the space community engages with artists and the ways in which substance is given to the aspiration for ‘inspiration.’

2.3 Public engagement

Seeking to address this, in 2015 the UK Space Agency announced a funding call for new work in visual arts and creative technology, seeking ‘original ideas which give new perspectives on science, technology and exploration in a sociocultural context.’ [6] This was an effort to use art for more than ‘outreach,’ aspiring instead to a more meaningful ‘engagement.’

The UK’s National Coordinating Centre for Public Engagement gives a helpful definition of public engagement: “Public engagement describes the myriad of ways in which the activity and benefits of higher education and research can be shared with the public.

Engagement is by definition a two-way process, involving interaction and listening, with the goal of generating mutual benefit” [7] (emphasis added). In the context of the UK Space Agency scheme, we sought to foster a genuine two-way exchange between artists and the space community for mutual benefit.

3. Aleksandra Mir’s Space Tapestry

One of the projects selected for support under this scheme was Space Tapestry by Aleksandra Mir: inspired by the Bayeux Tapestry and the anonymous artists who depicted Halley’s Comet in 1066, it is a large-scale hand-drawn monochrome wall hanging which forms an immersive environment.

Mir brought together a team of more than 25 collaborators, aged 18–24, to collectively draw the work using Sharpie pens in her London studio. This team followed the artist’s design, but brought their own tendencies and styles to mark-making. Different textures are apparent in the finished work – giving it a depth and human-ness, reflecting the collaborative mode of its production.

There were broadly speaking three aspects to the involvement of the UK Space Agency: i. financial support; ii. introductions to potential collaborators to approach in the space community; iii. conversations between UK Space Agency and the artist: exchanging ideas on how exploration ‘works’ and the parallels or contrasts with artistic production.

The first two require little explanation: the UK Space Agency funds many activities and while placing grants with individual artists is somewhat different to managing contracts with industrial entities or research organisations, the same general principles apply (although the relatively limited funding the UK Space Agency provided here was not the total cost of the work; several other funding sources were also required.)

Similarly, identifying connections and making introductions between people within the space sector is a regular and commonplace activity for officers of a space agency. Less typical, less comfortable and more time-consuming was the third: commitment throughout the development of Mir’s work to discuss the conceptual and manifest links between her practice and that in the actual space sector.

4. The relation between space sector and artist

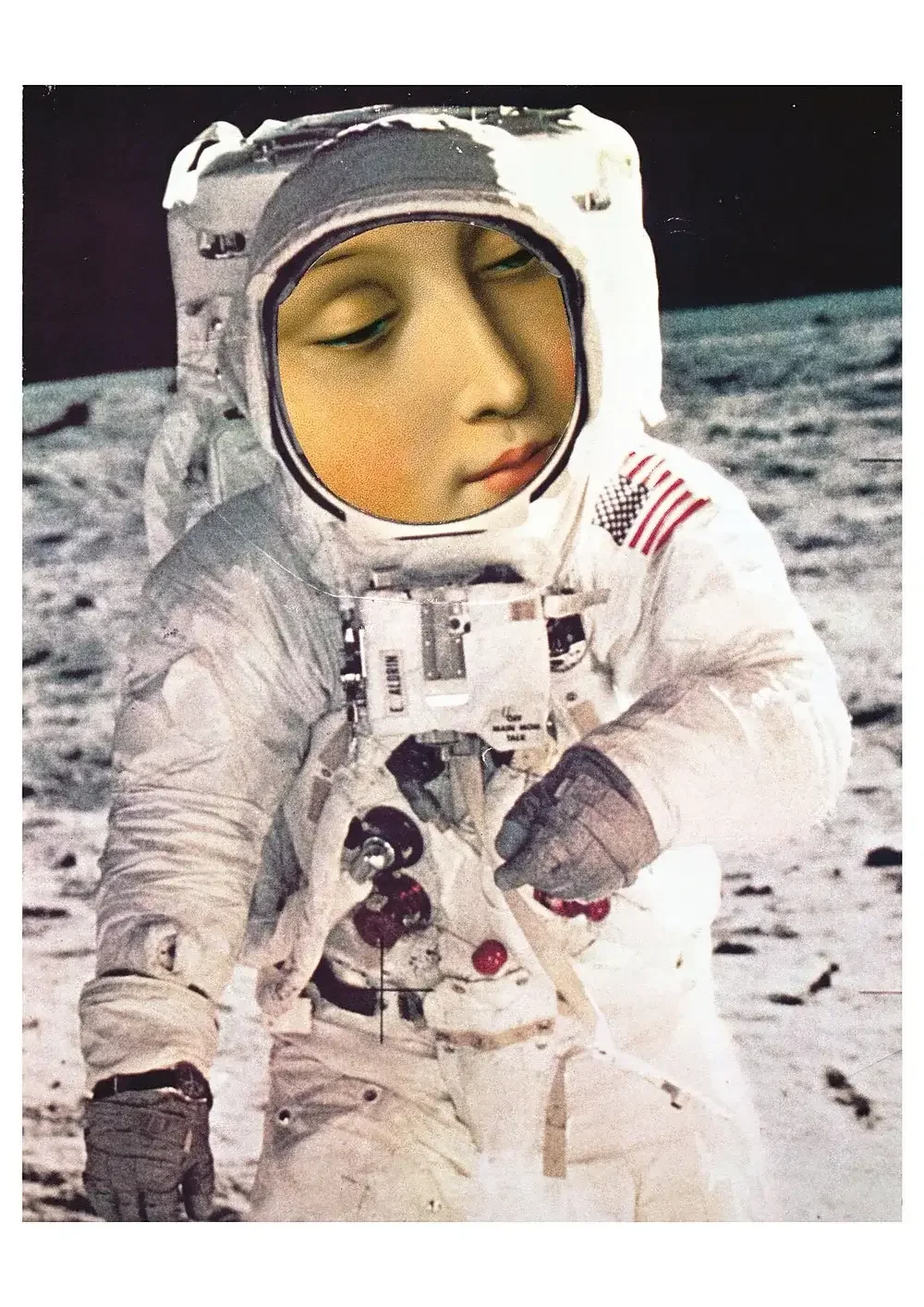

In August 1999, Aleksandra Mir had declared herself the First Woman on the Moon. This striking statement was amply evidenced through video and photography, whilst being evidently false. Her ‘moon landing’ was staged on a beach in the Netherlands: a moonscape was built with the aid of heavy machinery and a willing crew of helpers.

There are various themes at play: the distinction between versions of truth; the construction of competing versions of history; the role of women in science and technology. This work can also be seen as an illustration of the two versions of space: through one lens Mir is indeed the First Woman on the Moon; through another she is manifestly not. Mir herself has said that “I am interested in not only how images represent reality, but also how they produce reality in and of themselves.” [8]

A small but striking detail perhaps illustrates the point just as well: Mir had no idea at the time, and only learned some years later, that she was just 40km from ESTEC, the technical development and test centre of the European Space Agency. Along a relatively short stretch of the Dutch coast, two separate teams were immersed in their alternative versions of space, each in complete ignorance of the other.

For Space Tapestry, Mir took a different approach: to play on the representation of events as recorded through visual histories like the Bayeux Tapestry, to re-present the history of space exploration. This could have become another one-way transfer of ideas/imagery/concepts from one domain to the – but in practise relied on Mir immersing herself in the ‘other’ version of space: space-as-concrete-reality.

4.2 Engaging with the space community

Through conversation with myriad professionals from the space sector, recorded in the accompanying publication We Can’t Stop Thinking About The Future: Artist Aleksandra Mir Speaks with the Space World, Mir interrogated just what space exploration is; what it is for; and the ways in which distinct practices can respond to similar challenges.

In doing so, she forced those space professionals to likewise pause and reflect on the very same questions; to approach the challenge of space exploration not as engineers, scientists or administrators, but as humans engaged in a vast collective enterprise. Perhaps because of the separation of space-as-cultural-object and space-as-concrete-reality exist, Mir had spent her life thinking about space, but rarely engaging with those who manage actual space programmes.

Conversely, the UK Space Agency has devoted little resource to assessing its purpose and function on a philosophical level. Unavoidably, however, the work of a space agency is grounded in human culture: it responds to the challenges, biases, preferences and innate assumptions that guide all decision making, in pursuit of necessarily narrowly prescribed objectives. It would not be practical for every project officer in an agency to spend days unpicking the meaning of reality – but being occasionally forced to confront the position of our work in society can improve decision making.

6. Conclusions

Space agencies around the world, including the UK Space Agency, already make great use of the many ways in which space exploration can excite and inspire. It is natural that agencies established with the express purpose of delivering space activities see art first and foremost as a means to further that agenda.

Space agencies can however choose to expand their viewpoint and see art as a means to further that agenda and as a route to critical reflection, enhancing understanding of the role of space in society.

There is no suggestion that two-way engagement between space agencies and artists can resolve the centuries-old divide between art and science – but explicit recognition of the dual existence of space can be an interesting and enriching first step in confronting the purpose and societal significance of the programmes we deliver.

Doing so requires more than financial investment in a few art projects. Creativity is possible within the necessary constraints of government space programmes – but a modest investment of time is critical, as is a willingness to be uncomfortable and work differently.

5.2 Space programmes as both cultural object and concrete reality

Space programmes through time become cultural artefacts themselves. The One Small Step to Protect Human Heritage in Space Act [9] recently introduced in the Senate of the United States seeks, through legislative means, to preserve and protect the historic Apollo 11 landing site. Space reality then, through the passage of time, becomes at once cultural object and historical reality.

The enduring meaning of Apollo 11 is much more than its contribution to subsequent scientific discovery and technological developments; its socio-cultural significance vast; through the passage of time and its situation in culture, this mission is simultaneously space-as-cultural-object and space-as-concrete-reality. We cannot have one without the other.

Greater engagement with domains beyond STEM can help space agencies understand this and reflect not just on the immediate returns on investment, but our deeper purpose in supporting a deeper understanding of (following Kant) what it true, what is beautiful and what is good.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Aleksandra Mir for the conversations and challenges (and of course the art); to Sue Horne for her open mind and patience; to Marek Kukula for the early support; and to Vivienne Kuh for the introduction to, among other things, theories of Public Engagement.

References

[1] K. Malevich, The Non-Objective World, P Theobold, Chicago, 1959 (trans. H. Dearstyne; originally published in Russian in 1926)

[2] J.M. Bernstein, The Fate of Art: Aesthetic Alienation from Kant to Derrida and Adorno, Polity Press, Cambridge, 1992

[3] C. Janaway, “Knowledge and Tranquility: Schopenahuer on the value of art”, in: D. Jacquette (ed.), Schopenhauer, Philosophy and the Arts, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1996, pp. 39.

[4] C. Sagan, “Can We Know the Universe?” In: M. Gardner (ed.), The Sacred Beetle and Other Great Essays in Science, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1985

[5] A. Miller, Colliding Worlds: How cutting-edge science is redefining contemporary art, W.W.Norton, New York, 2014

[6] UK Space Agency website, Announcement of Opportunity, June 2015, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/440943/ao_hsf_mg_outreach.pdf (accessed 26.09.2019)

[7] NCCPE website, What is Public Engagement?, https://www.publicengagement.ac.uk/about-engagement/what-public-engagement (accessed 26.09.2019)

[8] A. Mir, UK Space Conference Talk, 14 July 2015, https://www.aleksandramir.info/projects/uk-space-conference-talk (accessed 26.09.2019)

[9] S.1694, One Small Step to Protect Human Heritage in Space Act, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/1694/text (accessed 26.09.2019)